Artist: Ting Yin Yung (1902 – 1978)

Title: Ting Yin Yung: Catalogue Raisonné, Oil Paintings

Format: Print, single volume

Languages: English and Chinese

Publisher: Hatje Cantz

Printer: DZA Druckerei zu Altenburg GmbH, Altenburg, Germany

Publication Date: September, 2020

Availability and Price: Edition of 1,000 (in print); € 88

Objects: 301 oil paintings, 1925–1978

Object Fields: Work title, year, medium, size, signature, provenance, exhibition records, publishing records

Supporting Documentation: Essay, chronology, and appendices: a visual index of double-sided paintings, works known only from published illustrations, works known only from photographs, exhibition history, writings by the artist, bibliography

Database: FileMaker

Project Establishment Date: 2000

Organizer and Co-Publisher: Li Ching Cultural & Educational Foundation

Active Project Term: approx. 3 persons full-time over 3 years

Project Team: Rita Wong, Dani Lee, Heli Hsu, Crystal Xiong, Shihwei Liang, Suzanne Wang (Authors), Joanne Martindale Allen, Li Ling Hsieh (Editors), Yujun Yang (Translator), Dan Chang (Copyeditor), Glenn Suokko (Graphic Design), Dani Lee, Richard Viktor Hagemann (Coordination), Thomas Lemaître (Production)

_____________________________________________________

Interview with Rita I-Wong, Chair of the Li Ching Foundation, Taiwan

As the Ting Yin Yung catalogue raisonné of oil paintings is the latest in a series of catalogues raisonnés organized by the Li Ching Cultural and Educational Foundation, how has this project benefited from the experience gained through prior projects?

We have accrued accumulative experience from the previous projects, namely creating a methodology for catalogue entries, securing copyright permission for image reproductions, organizing archival material, and resolving issues pertaining to a bilingual publication. The primary difference with this project has been the abundance of digitized material available on the internet. While enhancing the quality of our research, this also created heavier editing duties.

How did the work of the catalogue raisonné progress in the time between its launch and when the project became a full-time concern?

As with all catalogues raisonnés, the most tedious and time-consuming phase was locating the available works and physically inspecting each one to finalize inclusion in the catalogue. Having worked at Sotheby’s for 20 years and being the person responsible for establishing auctions of Chinese modern Western-style art in Asia, I was privileged to know not only the artists’ families, but also most of the major collectors and collections in the region. In addition, as Ting was a teacher of art, his many students helped in gathering information that has led to the discovery of paintings. I started collecting material on Ting while still at Sotheby’s and when I retired in 1998, I worked on 5 other catalogues while keeping Ting on the back burner. It wasn’t until 2016 that I was able to focus more on the Ting project.

If catalogues raisonnés were exclusively agents for the art market, the first Ting oeuvre catalogue might have documented the ink paintings. Why catalogue the artist’s oil paintings?

Ting started his artistic career in oil paintings. It wasn’t until the 1950s that he started using traditional Chinese ink and brush. Nonetheless, he is most well-known for his ink paintings, which made organizing and introducing his oil paintings in a complete manner all the more necessary.

Compiling a catalogue raisonné of his ink paintings is not out of the question. We did the catalogue raisonné of Sanyu’s watercolors and drawings, which number in the thousands. Even though there are even more ink drawings by Ting, the fact that they were all done during his Hong Kong years will make the project—should we decide to undertake it—a bit more simple.

What research resources were most critical for the catalogue?

Getting authorization from Ting’s daughters to do the project was the critical first step. They provided invaluable material, including photos of early and missing works, manuscripts, private documents, newspaper clippings, diaries, and letters. In addition, we received assistance from Ting’s students, collectors, scholars, museums, and auction houses.

Our research team also played an important role in setting up the Ting archives. Utilizing the physical and digital collections of museums, libraries, and archives, our young and resourceful team unearthed a considerable amount of important material as well.

Did the available documentation inform the content design of the chronology?

Yes, relevant documentation and archival materials were the guiding force to the content and design of the chronology. Given the complexity of the Republican era in Chinese history and the abundance of available historical material, determining important narratives that highlight Ting’s life, career, and art appropriately was a critical aspect of creating the chronology.

In presenting the catalogue raisonné in both English and Chinese, what romanization standards did you develop while accounting for differences between Mandarin and Cantonese?

In this volume, we mainly followed the personal preferences instead of using the commonly accepted hanyu pinyin system to romanize Chinese characters. Hanyu pinyin is based on the Mandarin pronunciation of Chinese characters. Given that many people discussed in this volume are Cantonese, it’s inappropriate and incorrect to use the hanyu pinyin to romanize their names. For example, following the artist’s choice, this volume uses Ting Yin Yung instead of Ding Yanyong, the hanyu pinyin romanization.

Self-Portrait (CR 73), 1925. Courtesy of the Ting Family.

How varied were Ting’s methods of signing, inscribing, and dating his oil paintings?

The earliest painting in this volume is a self-portrait (no. 73) completed in 1925, during his final year at the Tokyo Fine Arts School, on which he signed “Ting” in English cursive script and dated “1925”. The remaining paintings are from after 1949. During the 1950s, the artist signed his paintings “Ting” or “Y. Ting” in English cursive script and dated them according to the binary system promoted by the Nationalist government, which uses 1911, the year of the founding of the republic, as the base year.

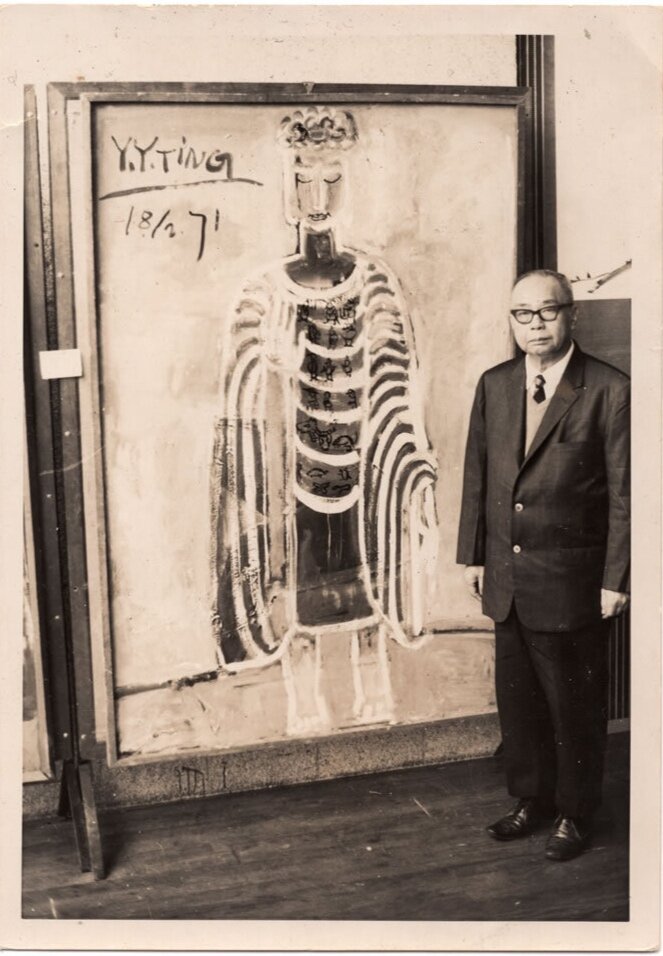

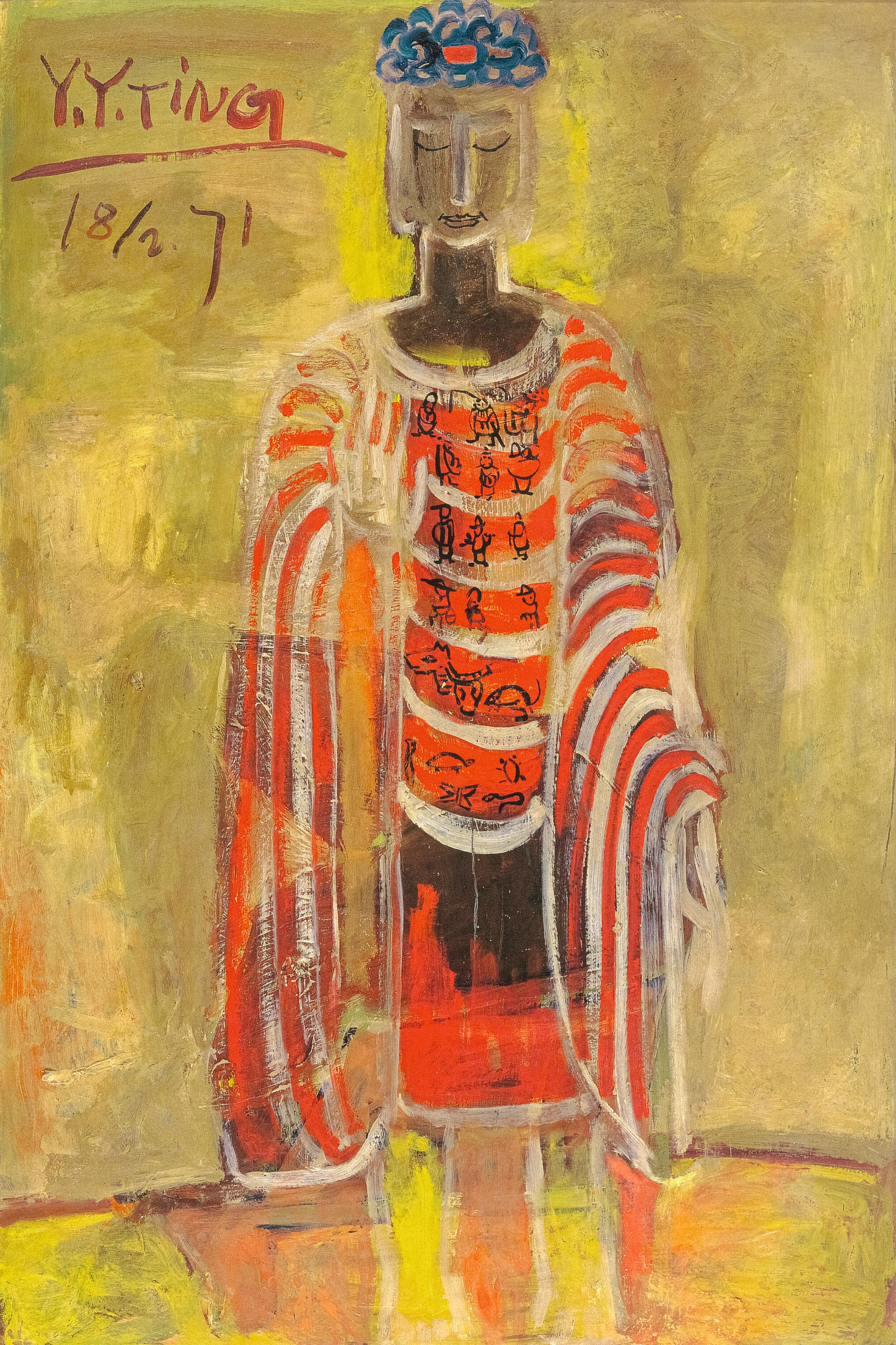

After 1958, there was a lull of two years with no known oil paintings. When he resumed in 1961, while he signed his paintings as before, he dated them according to the international system used today. Starting in 1963, a year when he was most actively painting in oils, he started to sign his name in capital letters, “Y. TING” or “Y. Y. TING,” frequently adding day and month to his dating.

Why group the paintings according to subject matter?

The 301 paintings in this volume are organized according to subject matter—archaic and symbolic motifs, portraits and figures, nudes, still lifes, landscapes, and primitive, religious, and traditional motifs (appearing in this sequence within the catalogue). We also take into account chronological developments within each genre, as it is hoped that in this framework, certain iconographic and stylistic relationships will be revealed that enable a better understanding of the artist’s creative impulses and demonstrate parallel developments and interplay with his ink paintings and seal carving—a fascinating and compelling dynamic of Ting’s life and art.

Woman In Red (CR 112), 1969. Courtesy of the Ting family.

The catalogue essay and chronology draw a number of connections between the artist and his influences, contemporaries, and students. What resources would you suggest for further reading on artists associated with Ting such as Bada Shanren, Chen Shu-jen, Chen Shih Wen, and Mok E-Den?

To name a few, Wang Fanyu (王方宇)’s Master of the Lotus Garden: the Life and Art of Bada Shanren, 1626-1705 (1991) is one of the must-reads; regarding Kao Jianfu and Chen Shu-jen, Li Weiming (李偉銘)’s research and editorial works deserve special attention; three institutes of the Chinese University of Hong Kong released a collection of Chen Shih-Wen’s essays in 2016, which is the first book featuring Chen’s art theory; for catalogues of Mok E-Den’s works, visit http://www.mokeden.com/publication.

As the Ting catalogue raisonné and other scholarly works expand the possibilities for the study of modernist Chinese art history, what subsequent projects would you like to see come to life?

The era which we are concerned with was a turbulent one for China – the end of dynastic rule and the beginning of a nascent Republic, 1911-1949. This was a sadly short period of time, but one that witnessed artists struggling to redefine the nation’s artistic tradition. Our focus has been on those artists who chose to travel abroad to learn the ways of the West in the hopes of revitalizing what to many was a moribund artistic tradition. Some met with success while others didn’t, but all followed their calling with a passion and devotion unseen in many other artistic cultures. We will endeavor to dedicate our time and resources to documenting the work of one of these artists every year.

_______________________________________________________

To learn more, visit tingyinyung.org or contact the Li Ching Cultural & Educational Foundation at info@liching.org.

Interview conducted by Carl Schmitz, Director of Communications and Publications